Traditional Lakota culture places a high value on life. Hunters only took from the great buffalo herds on which the tribes depended when meat was needed, and no part of the animal was wasted. In battle, to count coup was to touch an enemy with a stick and escape uninjured. This was considered a higher honor than killing the enemy.

But make no mistake - the Oglala Lakota also were known as fearless warriors. There is a legendary Lakota rallying cry popularized by the great Oglala war chief Crazy Horse, one he is said to have used at the Battle of the Little Bighorn: “Today is a good day to die!”

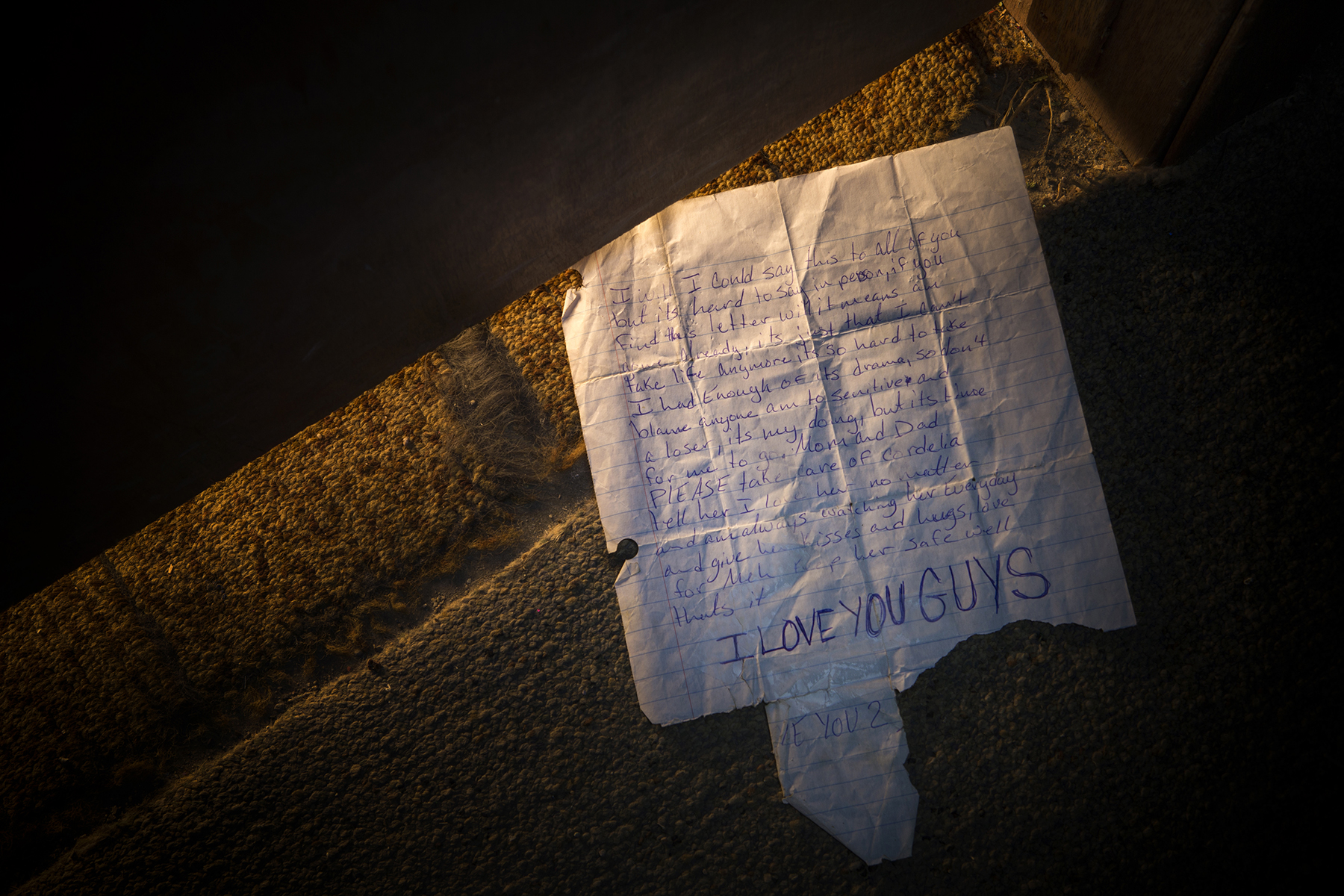

It has been more than a century since the Wasichu, or one who takes the best meat for himself, came from the east, slicing up the great prairies with trails, fences and railroads. But now, 128 years after the white man confined the Oglala people to the Pine Ridge Reservation, death lurks around every corner. Life expectancy for a Pine Ridge male is the lowest in the world. Suicide rates dwarf national averages.

These issues are inseparable from alcoholism, which perpetuates hopelessness and despair. Drunk drivers endanger every vehicle on the narrow roads and Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders affect youth at disproportionately high rates. And much of the alcohol comes from Whiteclay, Nebraska.